I've recently finished reading "x64 Assembly Language Step-By-Step Programming with Linux" by Jeff Duntemann. I found it to be a great introductory book to x64 Assembly programming. (The book also has a clear and simple explanation of how computers work from transistors, binary and hexadecimal, to memory addressing. But this isn't what I'll be writing about today.) After finishing the book, I decided to embark on a quest to implement a simple terminal walker game as an x64 Assembly program.

The "game" is run in a Linux terminal with the default columns and rows setting of 80 columns and 24 rows. The terminal screen shows a blank game board with the "@" character representing the player's character in the game. The player can move their character around the game board using the arrow keys on the keyboard. Moving the character around will leave behind a trail of where the character has been. This trail is shown as the "." character. The player is able to reset the game by pressing the "spacebar" key. The player can exit the game by pressing the "escape" key. Like I said, it's just a super duper simple terminal walker game.

In implementing this game I had to research and work with things that I don't often encounter in my day to day job. I had to use Linux system calls to read/write bytes of data to/from the terminal (as well as do other things), use ioctrl and termios to get and set terminal configs, and plan out the data structure of the game board in the memory.

The game need to be able to read user keystrokes and print out the ASCII characters on the terminal screen, therefore I needed to use system calls to call the Linux kernel functions: sys_read and sys_write.

The Linux kernel provides a lot of useful functions that could be called from Assembly programs. The calling convention of these functions are standardised in the System V Application Binary Interface (ABI). System calls in x64 are made by passing the kernel function ID and it's parameters into registers, then calling the "syscall" instruction. Each kernel function is associated with a unique ID number. The function ID is stored in the RAX register, while the parameters are stored in the registers: RDI, RSI, RDX, R10, R8, R9.

The sys_read system call can be use to read data strings from a File Descriptor (fd). The fd I'm using to read data in from the user keystroke in the terminal is Standard Input (STDIN). sys_read requires a memory address of where to store the data, as well as the amount of bytes to read from STDIN. The sys_read call I'm using to read the user keystroke looks like this:

I'm reading in 4 bytes because the input_mem_address memory space that I've allocated is 4 bytes in size. The actual keystroke data size is actually only 3 bytes, but I've allocated an extra byte so that the data could fit inside a 32 bits register. 3 bytes is 24 bits, and there are no 24 bits register for us to work with. Also, when using the comparison instruction, "cmp", to identify which keystroke was read, the instruction can only take in either 8, 16, 32, or 64 bits register/memory/immediate data. If I were to store the keystroke data in a 3 byte memory storage, I would need to call "cmp" 2 times: one 16 bits comparison, then one 8 bits comparison.

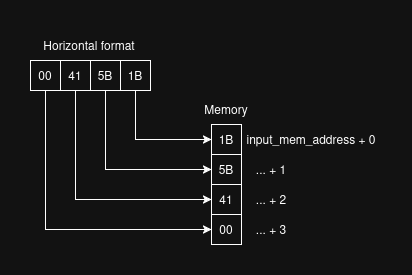

The keystroke of the arrow keys are three 8 bits Escape sequences, while the escape and spacebar keys are just a single 8 bits ASCII value. Escape sequences looks like this: "<ESC>[A". This particular one is the escape sequence of the up arrow. When translated to ASCII values it looks like this (in base 10 decimal): 27 91 65, in base 16 hexadecimal it looks like this: 1B 5B 41. Since my x86_64 Intel CPU (and the majority of CPUs) uses little endian, the least significant byte of the data is stored in the smallest memory address. The least significant byte of the up arrow escape sequence is 1B, therefore it'll be stored in the smallest address in memory. The next one in memory is 5B, then after that is 41. When written out in a horizontal format it'll look like this: 415B1B. This is because in the horizontal format, the smallest address is on the right side, while the biggest is on the left side.

The opposite of a read, is a write. The sys_write system call can be use to write out bytes of data to specific file descriptors such as Standard Output (STDOUT) and Standard Error (STDERR). In the context of this terminal walker game, I'm using it to write out the game board to the terminal screen. The whole game board is a string of data stored in the memory. It works like a video buffer, where the game program make changes to the game board string in memory, then writes it out to STDOUT via sys_write. The sys_write call I'm using to send the game board buffer to STDOUT looks like this:

Register RSI need to contain the memory address of the game board string. Register RDX need to contain the length of that game board string. Length meaning how many bytes the string consists of. For example, if the game board string consist of 10 bytes of data, then it's length is 10. RDX actually just tells sys_write how many bytes of data to send out to STDOUT, so if we only want to print out half a game board, then we would put 5 in RDX. The default STDOUT file descriptor points to the terminal screen, therefore the game board will be written out to the terminal. As for the structure of the game board string, I'll cover that in the last section of this blog.

So far, I've only got experience with Assembly and system calls in Linux, I don't know what's the equivalent in Windows. I'll note that as something to look into in the future.

The terminal walker game takes user input keystrokes to control the user character on the screen. By default the terminal is set in Canonical mode. In this mode, user input doesn't get sent to STDIN until the user press enter/return. This isn't what I want for the game. I want the game to read the keystroke as soon as they've been pressed by the user. The terminal's Raw mode provide this functionality.

ioctl is a system call that can be use to control IO config of the virtual terminal device. termios is a library that can be use to retrieve and set specific terminal config. To set the terminal to use Raw mode, both the system call and the library must be use together.

Before going any further, I'll be honest and say that I don't quite fully understand a 100% about the ioctl system call and the termios library yet. I've only researched enough about them to be able to get the game working. I'll be adding them to the list of things I need to study about the Linux OS.

The terminal config, in termios, are controlled via bit flags. Each flag indicate whether a feature is enabled (set, 1) or disabled (cleared, 0). To set the terminal in Raw mode, the ICANON flag need to be cleared. There's also another flag that need to be cleared as well: the ECHO flag. If the ECHO flag is set, then every keystroke the user input will also be displayed in STDOUT (i.e. echo to STDOUT).

ioctl system call is use to retrieve the current terminal configuration. The retrieved terminal configuration is stored in memory and the game make changes to the feature bit flags, then call ioctrl again to set the new terminal configuration. The system call to retrieve the current terminal configuration looks like this:

The system call to set the terminal configuration looks like this:

The parameter in register RSI is the operation code of the driver. It is a 32 bits constant value. Both 0x5401 and 0x5402 are operation codes for the terminal driver to get and set the terminal configuration. Operation codes are documented here: https://manpages.ubuntu.com/manpages/trusty/man2/ioctl_list.2.html

Once the terminal configuration has been retrieved, the ICANON and ECHO flags can be cleared. The terminal configuration consist of 4 flags string, each representing a specific terminal mode: input, output, control, and local. Each flag mode is a double word string (4 bytes, 32 bits). Within each flag mode, each bit represent a feature. Therefore, a single flag mode can have up to 32 features associated with it. The ICANON and ECHO feature is associated with the local mode flag. The feature flags are listed and described in the termios man page: https://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man3/termios.3.html under the c_lflag constant. The feature flags are listed in order from the least significant bits (top) to the most significant (bottom). Therefore, ICANON is the 2nd bit in the flag constant, and ECHO is the 4th bit in the flag constant. Using bit masking, the two flag bits could be cleared like this:

and byte [c_lflag], 11111101b ; Disable ICANON flag bit. (2nd bit) (0FDh)

and byte [c_lflag], 11110111b ; Disable ECHO flag bit. (4th bit) (0F7h)

; or better yet, they could be combined into a single operation:

; and byte [c_lflag], 11110101b

A side note. Writing this blog now, I thought of a better way to restore the terminal configuration. When I initially wrote my game program, I allocated 2 strings to memory, one for the original terminal config, and one for the config that the game make changes to. The original config is pass to ioctl system call at the end of the program to restore the terminal config to whatever it was before the game started running. The better way, would be to allocate just 1 string to store the config, then modify the config back to its original state at the end of the program. This way I can reduce memory storage and the time it takes to retrieve those memory into the CPU. Something like this:

and byte [c_lflag], 11110101b

; .......

; Restoring terminal config

or byte [c_lflag], 000001010b

When exiting the game, the terminal config need to be restored. ioctl is called again to set the terminal configuration back to its original state.

The default terminal screen consist of 80 columns and 24 rows. 80 x 24 = 1920, this means that there are 1920 cells/positions available on the game board. The characters I'm using to visualise the game board are all normal ASCII characters:

Since they're all ASCII characters, they can be stored in a single byte, therefore I have to allocate 1920 bytes of memory to store the game board....

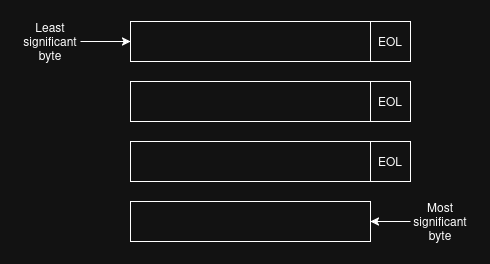

Now, this isn't quite right yet, because the allocated memory doesn't have any space to store the formatting ASCII character: EOL. EOL is required at the end of each line, after the 80th column, to begin a new line in the terminal screen. This means that instead of allocating 80 columns for each row I have to allocate 80 + 1, where the extra column byte is for storing the EOL character. I allocated 81 columns for each row, except the last row, because the last row doesn't need a new line. The EOL ASCII character has a decmial value of 10.

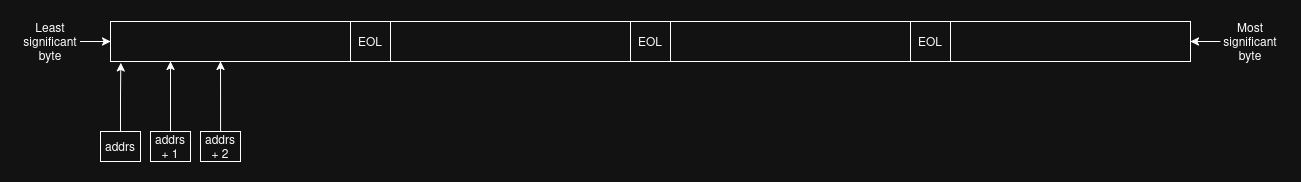

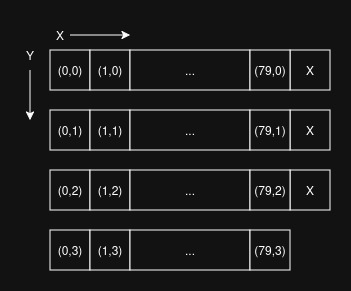

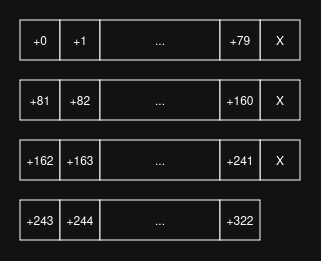

When the rows are arranged where the head of each row is connected to the tail of the previous row it shows what the game board data structure looks like in the allocated memory.

The game board is 2 dimensional, meaning that the user character is able to move in 2 directions, either x (horizontal) or y (vertical). I implemented the game program position (0,0), where (x,y), to be the top left corner of the terminal. The max horizontal position that the user character can go to is x = 79, because position x = 80 is reserved for the EOL character. The max vertical position that the user character can go to is y = 23.

To correctly access each position of the game board in the memory, the position coordinate must be translated from (x,y) to the effective memory addressing offset value. The offset value is how many bytes the specific position is from the starting memory address. In the diagram below, the coordinate (0,0) has an offset value of 0 from the starting memory address, while the coordinate (79,0) has an offset value of +79. I'm using the formula (y * COLS) + x, where COLS = 81, to calculate the the effective memory address offset value. The offset value can be added to the starting memory address to get the position in memory that the (x,y) coordinate refers to.

The assembly code used to do the calculations and effective memory addressing looks like this:

mov ah, COLS

mul ah ; ax = al * ah

and bx, 0FFh ; Mask bx to get only the lower bits i.e. bl.

add ax, bx ; ax = ax + bx

and eax, 0FFFFh ; Mask eax to get only the ax bits.

; eax consist of 4 bytes, we're masking it

; to get only the lower 2 bytes of data

; which is the ax register.

mov byte [TermBuffer + eax], cl ; Use eax to do effective

; addressing instead of ax

; because 16 bits registers

; can't do effective

; addressing.

I found it quite interesting how often bit masking is used in assembly programming to satisfy the instruction sets and their register size requirements.

I found this project, rather than being an exclusive exploration of x64 Assembly, to be an equal part exploration of both x64 Assembly and Linux OS. The Assembly program can do so much in isolation without the help of Linux system calls and libraries.

I would say that I had a pretty good time implementing this game. Spent few hours a day on it for about 3 days. The majority of the time spent was on researching how to set up Raw mode in the terminal to take user keystroke input. This solidifies the fact that there's a lot more for me to learn on the OS layer to be able to fully utilise the power of the OS and the computer.